Filtering by Tag: Practicing

Going on Autopilot

“Going on autopilot” doesn’t sound good. It sounds mechanical, unfeeling, antithetical to bringing an audience on an emotional journey. To truly affect someone, you have to be, well, conscious, right? In most cases, sure. But sometimes, things get scary—moments at the extremes of dynamics and range, moments of unusual technical and expressive demands. At those times, when your mind is distracted by sheer terror, the ability to let your training take over is indispensable.

Let me clarify what I mean. By autopilot, I mean ingraining your technical and musical mission (to co-opt a phrase from Daniel Matsukawa) so firmly that, no matter what else is going on in your mind, your body knows what to do. Most of us experience performance anxiety at least some of the time, whether it be in an audition or a high-pressure performance. Of the variety of ways to deal with that, and without judgment of any of them, I’ve found this to be the strategy from which I learn the most. By confronting my nerves head-on and finding practice strategies that enable me to (hopefully) play well in spite of them, I learn about myself and am able to put that knowledge to use in future high-stress situations.

What does this mean in practical terms? Practice a piece in the wrong key. Run around the room, then play before you’ve had a chance to catch your breath. Play an excerpt well five times in a row, consciously noticing the tension that creeps in as you get closer to your goal. All of these make your life more difficult in the practice room, so that playing under normal circumstances becomes easier. We don’t want to only be able to play a passage well when we’re at our absolute best—comfortable, warmed-up, playing in the privacy of the practice room. We want our preparation to extend beyond the reasonable expectation of what we’ll have to do—we have to be better than the demands placed on us, because only then can we expect to play well in difficult situations.

This extends equally to one’s musical purpose. Making music is not an intellectual exercise, but many aspects of one’s musical goals can be quantified, and we can train ourselves to replicate them under pressure. A fantastic quote by Marcel Tabuteau appears in the liner notes to David McGill’s seminal orchestral excerpts CD: "If you think beautifully, you play beautiful [sic]. I believe to play as you think more than to play as you feel because how about the day you are not feeling so well?" It is precisely those days that we’re talking about. Mr. Tabuteau is referring to the ability to make music under any circumstances.

Gradually, we learn what strategies give us the ability to function on autopilot when necessary. We grow in our confidence that our preparation is sufficient—focused, intense practice that has done as much as possible to maximize the odds that we’ll play well, even if we’re a roiling mass of fear on the inside. Ultimately, the audience doesn’t care what is or isn’t difficult. That’s our problem, and it’s our responsibility to take the steps necessary to provide the insurance that, when the chips are down, we can still depend on our preparation to carry us through.

Why Fundamentals?

Fundamentals—scales, long tones, and the like—are boring. OK, I don’t actually believe that, but it’s a pretty widely-held opinion. So why do we do them? Moreover, in a time when we often hear that today’s young musicians “can play the instrument better than ever, but just aren’t musical,” what’s the benefit to focusing on things that are, by nature, basically inexpressive?

In short, it’s all about the music. Ben Kamins is fond of pointing out that we don’t work toward perfect evenness in scales and etudes, obsessively poring over every tiny inconsistency, because that’s how we make music. We do it so that when we’re playing Tchaikovsky or Mozart or Verdi, it is not technical demands, but expressive goals that dictate our musical choices.

So we’re (hopefully) agreed that they’re important, but how can we keep fundamentals interesting? I think it boils down to a specific mindset: Fundamentals provide a tremendous opportunity for self-discovery.

Case in point: Recently, I decided that I needed to practice more long tones. I have never been particularly conscientious when it comes to long tones, because I’ve always found them to be discouragingly difficult. So, much like my longtime approach to reed-making, I just wouldn’t do them.

So here’s what I decided to do: I practiced them for five minutes. That’s it. Every day, I would add or subtract a minute, but I carefully kept my self-imposed time limit so reasonable that I had no reason not to do it. I knew that I wouldn’t attain “perfection,” but by putting in a consistent, measurable amount of work on a daily basis, I arrived at a satisfying substitute. The experience became about seeing how much I could learn in a finite amount of time. It became a journey of discovery, rather than perfection—and that is why we practice fundamentals.

How to Learn an Opera in Five (easy?) Steps

Mind the Gap

In my last post, I described how I got one paradigm-shifting piece of advice…and went completely overboard with it. The story of regaining my confidence in the practice room is one that continues to this day.

It boils down to what Ben Kamins refers to as “starting from a point of success.” The thing is, we all know how we want to play. We all have an ideal we’re striving toward. But every day, we’re confronted with the reality of where we currently stand, and that reality almost never aligns with our ideal. There will always be a gap between those two points—where we are and where we want to be—and the question of confidence is really the question of how we choose to approach that gap.

One extreme, which I chose in high school, is underestimating where one’s limit is, and approaching it as cautiously as possible. This approach killed my confidence. The other extreme leads to misplaced confidence: denying that there is any gap at all—going full speed ahead, hammering through the most difficult passages without any regard for the sounds that are coming out of the instrument. I think it goes without saying that this is also a pretty bad option.

The key is balancing right on the edge of one’s abilities, but always starting from that point of success. One has to begin with something one can do, and gradually push out of one’s comfort zone. I still find this hard, since I can’t leave something alone until it’s as good as I can play it. I prefer to stay in my comfort zone, even when nobody’s listening.

I want to be very clear: I’m not suggesting less slow practice, nor am I advocating less time spent methodically, sometimes painstakingly, working through difficult passages. Quite the opposite—I’m advocating a straightforward appraisal of one’s strengths and weaknesses, and an approach to the weaknesses that is at once honest and confidence-building. Oftentimes that means spending a lot of time in the practice room with the metronome, but we also have to recognize when we can trust our years of training.

Now, I had to put in the work sometime—not to the extreme that I did, but I still don't regret that phase of my development. But now, when I practice an etude, I don’t always go bar by bar at the slowest tempo I can stand. I've done that work (and then some). Because, you know what? It's kind of fun to start near my limit and see how far I can push myself today.

The Balancing Act

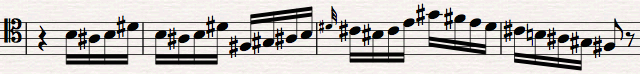

My practice revelation came when I was a junior in high school. I was working on the Russian Dance from Petrushka for seating auditions in the (drumroll, please) All-State Orchestra. Every day, I’d sit down and start practicing with my metronome at 60, then gradually speed it up until I was at performance tempo. I’d feel good about it—I’d think I was making progress. But the next day, I’d try to see what I’d retained, and time and again, the answer was virtually nothing.

This cycle of one step forward, one step backward continued for a couple of weeks. I was starting to get, shall we say, frustrated? Distraught, perhaps. Demoralized, definitely. Then one of my (terrific) band directors recommended that I stick to one tempo per day, gradually increasing the metronome marking over a series of progressive practice sessions. That way, as I learned the passage at each day’s tempo, I wasn’t dependent on the process of starting slowly and speeding up. I increased the difficulty at a very slow rate and made sure I was confident at a single tempo every day.

This revolutionized my ability to learn difficult passages, but I took it too far. By the time I finished high school, I had reached a point where I felt I couldn’t play anything without starting very slowly and taking months to reach performance tempo…then, ideally, repeating the process to make sure I had really learned it. By doing this with everything I learned, I completely undermined my confidence in my ability to just play.

When I arrived at Curtis, one of the very first things I played for Bernard Garfield was one of his more difficult etudes (No. 20, to be exact). By that point, I had no idea how to learn something like it in a week. But the thing is, I could have done it if I had trusted myself. I could have practiced a narrow range of tempi every day—still slow, but allowing myself to inch up slightly over the course of each practice session. I could have assessed which passages I really needed to slow down, and which ones came more naturally. But I lacked a basic belief in my own abilities, so I insisted on coddling myself on every single note. I just didn’t have the time I thought I needed to learn something difficult, and I didn’t know how to compress my excessive practice regimen from months to a week. This was only the first of a series of challenges that would teach me the value of truly efficient, affirmative practice over the subsequent four years.

At the Met, I’ve played as many as six different operas in three days. Learning that much music requires the same peculiar balancing act. On one hand, one has to efficiently recognize and practice difficult passages, shining an unyielding light on things one can’t yet play. On the other hand, one has to do this in a way that increases (or at least maintains) confidence. In the practice room, the latter requires a delicate balance of self-awareness and practical considerations. More on that next time.